The catalytic effect of the metal bath on the zinc oxide reduction

Investigates how immersion in liquid metal baths accelerates the reduction of zinc oxide-bearing residues, combining controlled experiments with kinetic analysis to benchmark hydrogen-enabled recycling pathways.

- Journal

- Results in Engineering

- Year

- 2022

- DOI

- 10.1016/j.rineng.2022.100514

1. Introduction

The steel production in the electric arc furnace (EAF) generates electric arc furnace dust (EAFD), consisting mainly of oxidic compounds. The composition depends on the applied steel scrap and additives in the EAF [1]. The carbon steel production in EAF often melts zinc-coated steel scrap, generating an EAFD with a typical zinc concentration to 43 % of zinc in the form of zinc oxide and zinc ferrite [2]. Fe in oxidic form is another major constituent reaching values up to 45 % [2]. Other elements, such as Pb and Cl, cause EAFD to be classified as hazardous waste in industrialized countries [[3], [4], [5], [6]].

For economic reasons, the recycling of EAFD focuses on the recovery of Zn [7]. The current state-of-the-art recycling of EAFD is based on carbothermal reduction in the Waelz process [8,9]. Alternative industrial processes like ESRF [10], PIZO [11], and the pilot-scale tested 2sdr [12] are also based on the carbothermal reduction with the main reaction running via carbon dissolved in the metal bath, allowing for higher kinetics [13,14]. Although some data is available in the literature, no quantitative study is available that investigates the catalytic effect of the metal bath. The present study fills this gap with a kinetic investigation of the solid-liquid and liquid-liquid carbothermic reduction of ZnO, giving a better understanding of the reaction mechanism to help future process development. [9,15,16].

In process development, higher reaction kinetics enables higher throughput or smaller furnace dimensions, reducing specific operating costs. The catalytic effect of the metal bath may be considered in future developments of recycling processes. Carburizing of the metal bath is possible via the injection of coal. If biomass is used, the metal bath allows the development of a carbon-neutral process.

2. Materials and mMethods

2.1. Materials

The kinetic investigation used a synthetic slag mixture of quartz (SiO2), lime (CaO), alumina (Al2O3), and fluorite (CaF2). Before the actual reduction experiments, the slag components were melted together to a homogeneous phase to ensure maximum reproducibility. The added fluorite prevents slag foaming and improves the handling during the sampling process, improving the sample quality. A representative analysis of the slag can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Chemical composition and basicity of the slag.

CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaF2 | MgO | B2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

37.0 | 31.6 | 13.8 | 12.4 | 3,2 | 1.07 |

2.2. Methods

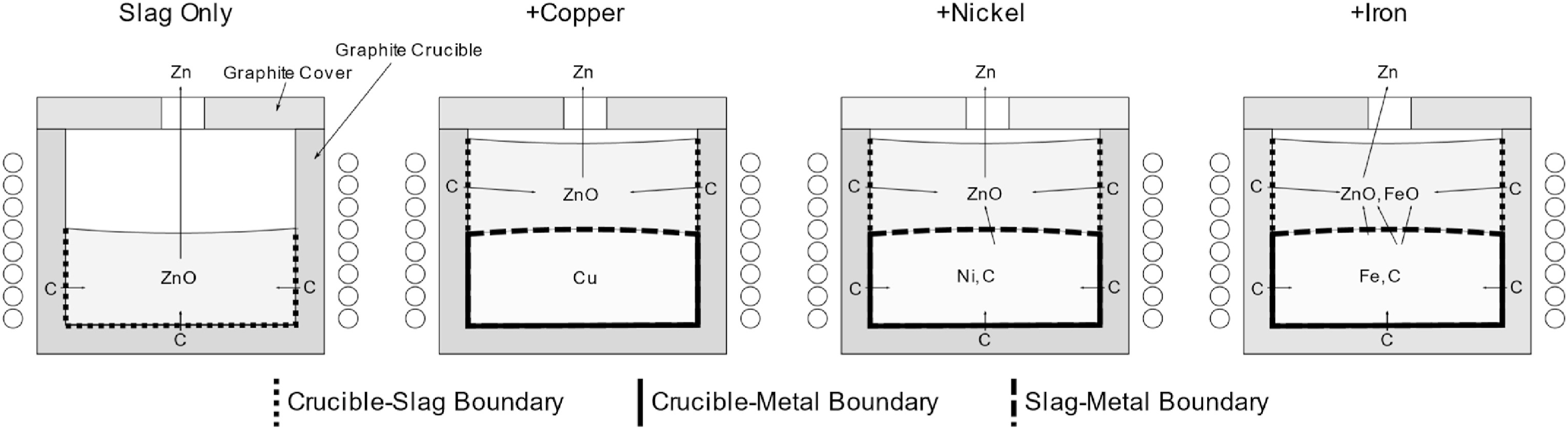

The experiments were carried out in a graphite crucible heated by an induction furnace in isothermal conditions at 1450 °C. The catalytic effect of the metal bath was investigated with 4 different experimental cases (Fig. 1):

Slag-only

Slag and copper

Slag and nickel

Slag and iron

The slag-only test represents the baseline and investigates the reaction rate between liquid slag and solid carbon. Copper partly covers the carbon-slag contact area, has no solubility for carbon, and does not react with zinc oxide, allowing to examine if the slag reacts differently at the bottom and the shell area. Nickel dissolves up to 2.1 wt.-% carbon at 1450 °C, allowing the slag to react with dissolved carbon, but like copper, nickel itself does not react with zinc oxide in the evaluated process conditions [17]. Iron has a solubility of 4.5 wt.-% carbon at 1450 °C and reacts metallothermically with zinc oxide. The experiments started with the melting of 2350 g inert slag and 3000 g metal. After a homogenization period of 30 min minutes at 1450 °C, 350 g of zinc oxide was added. Slag samples were taken in defined time intervals. The sampling of the metal was unreliable. The slag samples were analyzed using a scanning electron microscope with an energy dispersive x-ray detector (SEM-EDX). A detailed description of the experimental setup can be found in a previous publication [16].

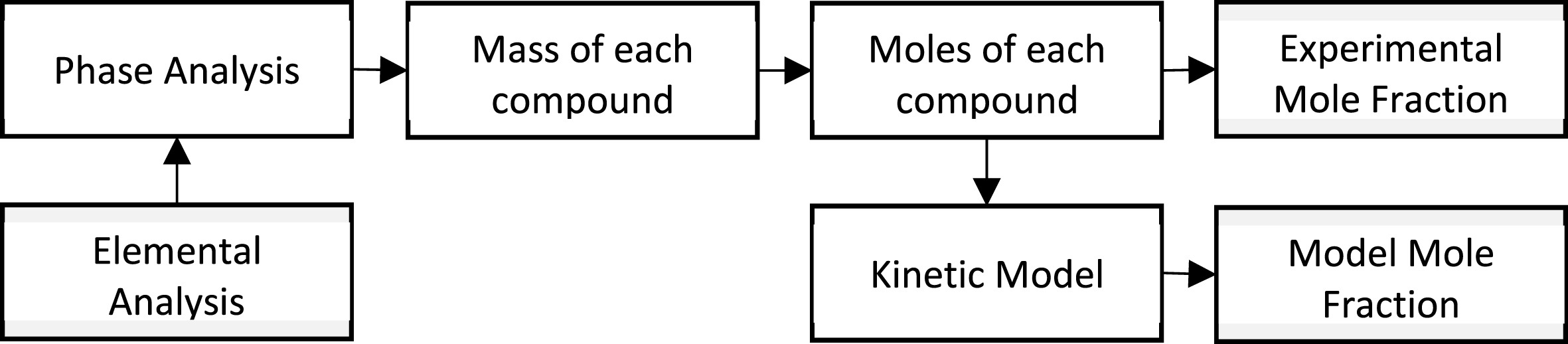

Fig. 2 summarizes the data processing and kinetic modeling methodology. The elemental analysis from the SEM-EDX detector was recalculated to phase analysis by assuming all F as CaF2; remaining Ca as CaO, all Si as SiO2, all Al as Al2O3, all Mg as MgO, all Zn as ZnO, and all Fe as FeO. The phase analysis and the weight of the inert compounds (2300 g) at the start of the experiment allow for calculating the mass of each compound in each sample. The mass of each compound was recalculated to moles of each compound, which were then used to fit the kinetic model.

Many kinetic investigations assume first-order rate expressions [18]. The present study does not study the reaction mechanisms in detail. Still, it develops a mathematical model that allows a comparison between the different cases to describe the catalytic effect of the metal bath quantitatively. Each experimental case required a different kinetic model. It was assumed that multiple reactions run simultaneously, having different reaction orders. Reactions between liquids and solids are often found to be first-order reactions. Therefore, the crucible shell-surface and the slag are assumed as first-order type, reactions between the crucible bottom-surface and the slag as zero-order type, and reactions between the liquid metal and the slag as second-order type (both reactions with dissolved carbon and metallothermic reactions). The results section discusses the reasons for this approach. Table 2 gives and overview of developed reactions. The models assume a constant surface area (and slag volume) which is a simplification because changing ZnO and FeO moles will lead to small changes in the area between the crucible shell and the slag. However, the influence of this simplification is small.

Table 2. Overview of the applied kinetic models (1–4) in the four different cases (1:Slag-only, 2:Slag-copper, 3:Slag-nickel, 4:Slag-iron).

Model A | |

|---|---|

Model B: | |

Model C: | |

Model D | |

With |

3. Results and discussion

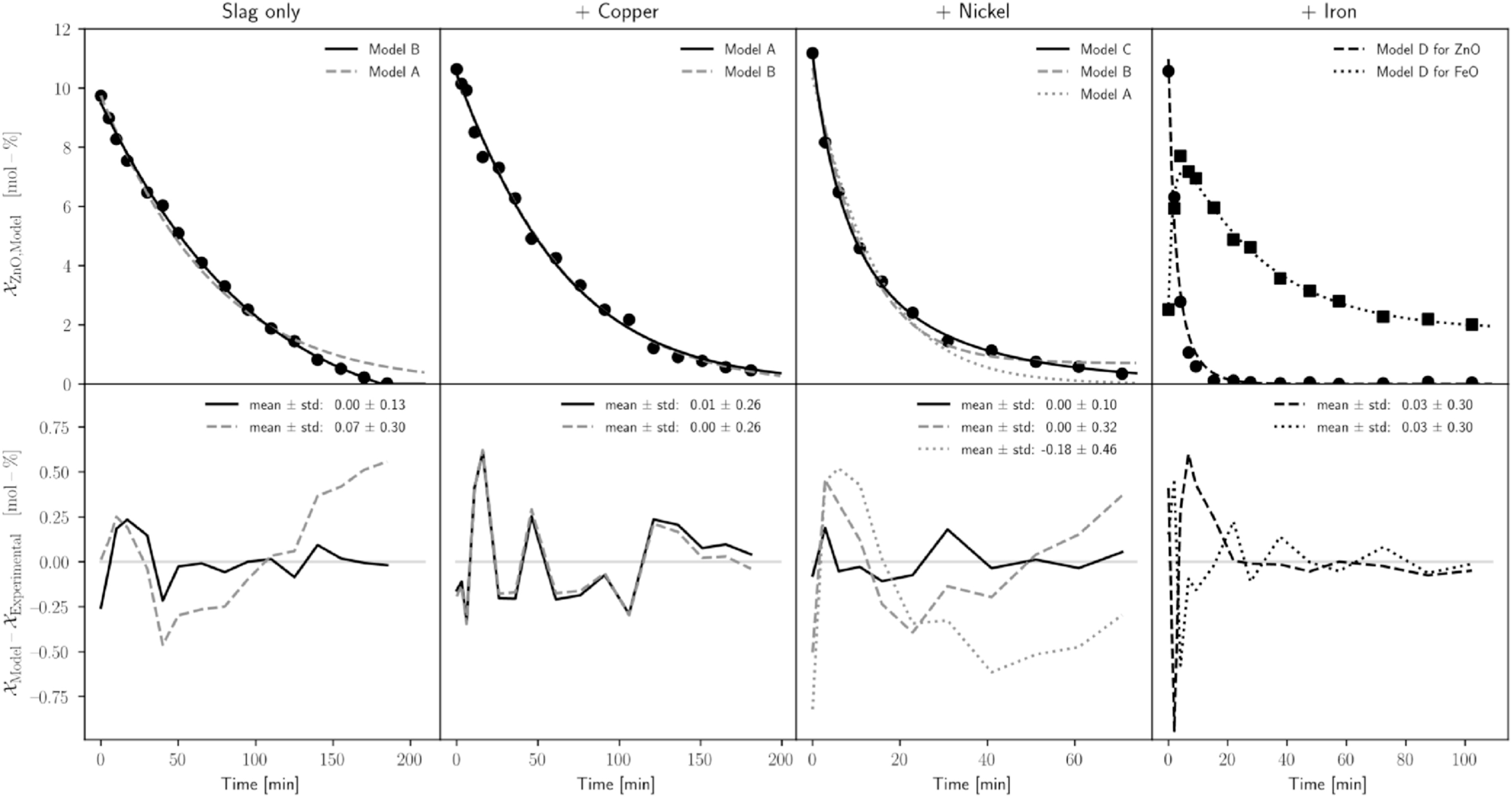

Fig. 3 a-d visualizes the results of the different cases showing experimental data and model values at the top and their deviation at the bottom. The best fits are displayed as solid lines, except for the case with iron where only one model is fitted.

3.1. Case 1 – Slag-Only

The slag-only trial in Fig. 3a shows the best fit for model B – zero and first-order reactions running parallel. Model A – only first-order reaction – overestimates the reaction rate when the ZnO concentration is high and underestimates the reaction rate when the ZnO concentration is low. A reason can be the different reaction mechanisms at the bottom and shell because gaseous zinc bubbles formed at the bottom of the reaction zone may be trapped until a critical bubble size is reached. Without creating additional surface area between the gas and the slag, gas bubbles cannot rise. But gaseous zinc can evaporate through the graphite crucible, explaining the observed reaction mechanism.

3.2. Case 2 – Slag and Copper

Copper below the slag reduces the contact area between slag and carbon from 481 cm2 to 198 cm2. The contact area between copper and slag is assumed to be inert. Fig. 3 b shows that model A and model B fit equally because the rate constant for the zero-order term is found to be close to zero. Therefore, the overall reaction is assumed to be of first-order type. This is in good agreement with the slag-only trial, where the zero-order reaction was assumed at the bottom of the crucible. In this setting, no reaction takes place at the bottom of the crucible because it is covered with inert copper.

3.3. Case 3 – Slag and Nickel

Using nickel instead of copper transforms the bottom phase boundary between metal bath and slag from an inert to a reactive area because nickel dissolves 2.1 wt.-% carbon at 1450 °C. The experimental data in Fig. 3 c suggests that the reaction between dissolved carbon in the metal bath and ZnO in the slag is not of first-order type because a first-order model must fit accurately. The reason is that the reaction at the shell surface is of first-order type. And multiple running first-order reactions are not distinguishable, resulting in a first-order reaction again. Similarly, assuming the metal-slag reaction as zero-order results in an accurate fit. However, considering the reaction between dissolved carbon in the metal bath and ZnO in the slag as second-order reaction results in model C, accurately describing the experimental data. The model deviation is determined by subtracting the experimental value from the model value. In this way, the mean deviation for model C reaches 0 ± 0.10 mol.-%, 0.18 ± 0.46 for model A and 0 ± 0.32 for model B over all data points.

3.4. Case 4 – Slag and Iron

The previous results were included in the iron and slag trial model. The metallothermic reaction between Fe and ZnO makes the model more complex. Reactions between slag and the carbon shell were assumed as first-order type, reactions between the metal bath and the slag as second-order type leading to model D. The metallothermic reaction between ZnO and Fe connects the otherwise independent differential equations forming a system of differential equations where the reaction rate of FeO depends on the ZnO concentration. Fig. 1 d shows the experimental data of ZnO and FeO and the values for the fitted model D. The sharp decline of ZnO during the first minutes is not mapped perfectly by the model, which results (including ZnO and FeO values) in a mean deviation of 0.01 ± 0.27 mol.-%. A possible reason is that the high reaction kinetics at the beginning change the rate-limiting step, such as insufficient heat transfer into the reaction zone.

Fig. 4a summarizes the results of all four cases shifted on the time axis to have a model ZnO value of 12 mol-% at t = =0 min. Fig. 4 b outlines the reaction rate in mol/min versus the molar ZnO concentration in mol-%. In the range of 12 mol-% and 3 mol-%, the reaction rate of the slag-only trial is lower compared to the copper trial, although the slag-only test has more contact area with carbon. This indicates that most of the reaction in the slag-only trial runs at the shell surface between the slag and the crucible. Copper dissolves part of the Zn, which is formed within the reaction zone.

Thus, copper acts as a buffer that accelerates the kinetics when the production rate of gaseous zinc is high but lowers the kinetics when the reaction rate is low. This is indicated by the slower reaction rate below 3 mol-% ZnO. For a better illustration of the catalytic effect of the metal bath, Fig. 4 c shows the reaction rates of trials 2, 3, and 4 (Cu, Ni, and Fe) relative to trial 1 (slag-only). The relative reaction rates change with the ZnO concentration. At 12 mol-% ZnO, the copper trial is around 1.5, the nickel trial 10, and the iron trial roughly 30 times faster than the slag-only trial. The gap decreases with lower ZnO concentration. This is caused by the fact that the slag-only trial follows zero and first-order models, compared to the metal bath trials, which follow first and second-order models.

4 Conclusion

The present study evaluates the catalytic effect of dissolved carbon in a metal bath compared to solid carbon for the carbothermic reduction of ZnO. The reaction via the metal bath increases the kinetics by a factor of 10 using a nickel bath and a factor of 30 using an iron bath. The reaction rate increase in the case of nickel originates solely from dissolved carbon in the metal bath. The rate increase in the case of iron originates from a more complex reaction system consisting of simultaneous running metallothermic and carbothermic reduction reactions. The reaction mechanism between metal bath and slag is second-order, meaning that its catalytic effect decreases with lower ZnO concentration. First-order reactions accurately describe the interaction between solid carbon at the shell and dissolved ZnO in the liquid slag. Solid carbon at the bottom reacts with ZnO in the slag as a zero-order reaction. We assume that this reaction is slow. Hence, gaseous zinc bubbles never reach a critical diameter to rise through the slag. Instead, generated gaseous zinc leaves the reaction zone by diffusion through the graphite crucible. In contrast, the reaction between dissolved carbon and ZnO at the metal-slag interface is fast, generating larger bubbles overcoming the critical diameter, which can rise through the slag. This study highlights that future process development should use the catalytic effect of the metal bath, resulting in increased process kinetics and optimized process economics.

Author credit statement

Manuel Leuchtenmueller: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition Ulrich Brandner: Conceptualization, Resources, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal analysis.

Funding

Christian Doppler Laboratory for Selective Recovery of Minor Metals Using Innovative Process Concepts, Chair of Nonferrous Metallurgy, Montanuniversität Leoben, 8700 Leoben, Austria.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

Anne-Gwénaëlle Guézennec, et al.

Dust formation in electric arc furnace: Birth of the particles

Powder Technol., 157 (1–3) (2005), pp. 2-11

Rainer Remus, et al.

Best available techniques (BAT) reference document for iron and steel production: industrial emissions Directive 2010/75/EU: integrated pollution prevention and control

EUR (Luxembourg), vol. 25521, (Luxembourg: Publications Office (2013)

Thomas Suetens, et al.

Comparison of electric arc furnace dust treatment technologies using exergy efficiency

J. Clean. Prod., 65 (2014), pp. 152-167

J.R. Donald, C.A. Pickles

Reduction of electric arc furnace dust with solid iron powder

Can. Metall. Q., 35 (3) (1996), pp. 255-267

Assis G., "Emerging Pyrometallurgical Processes for Zinc and Lead Recovery from Zinc-Bearing Waste Materials" .

G.M.S. Janaína, Machado, et al.

Chemical, physical, structural and morphological characterization of the electric arc furnace dust

J. Hazard Mater., 136 (3) (2006), pp. 953-960

M.H. Morcali, et al.

Carbothermic reduction of electric arc furnace dust and calcination of waelz oxide by semi-pilot scale rotary furnace

J. Min. Metall. B Metall., 48 (2) (2012), pp. 173-184

Xiaolong Lin, et al.

Pyrometallurgical recycling of electric arc furnace dust

J. Clean. Prod., 149 (2017), pp. 1079-1100

R.L. Nyirenda

The processing of steelmaking flue-dust: a review

Miner. Eng., 4 (7–11) (1991), pp. 1003-1025

Michio Nakayama

New EAF dust treatment process: ESRF

SEAISI Q., 41 (1) (2012), pp. 22-26

James E. Bratina, Kim M. Lenti

PIZO furnace demonstration operation for processing EAF dust thIS article IS available online at WWW.AIST.ORG for 30 days following publication

Iron Steel Technol., 5 (4) (2008), pp. 118-122

Gernot Rösler, et al.

2sDR”: process development of a sustainable way to recycle steel mill dusts in the 21st Century

JOM, 66 (9) (2014), pp. 1721-1729

W.J. gRankin, S. Wright

The reduction of zinc from slags by an iron-carbon melt

Metall. Mater. Trans. B, 21 (5) (1990), pp. 885-897

C.A. Pickles

Reaction of electric arc furnace dust with molten iron containing carbon

Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. (IMM Trans. Sect. C), 112 (2) (2003), pp. 81-89

Michael Auer, Juergen Antrekowitsch, Bernhard Voraberger, Krzysztof Pastucha, Uxia Dieguez, "2sDR - the Future Solution for Steel Mill Dust Recycling,".

M. Leuchtenmueller, et al.

Carbothermic reduction of zinc containing industrial wastes: a kinetic model

Metall. Mater. Trans. B, 52 (1) (2021), pp. 548-557

C.W. Bale, et al.

FactSage thermochemical software and databases, 2010–2016

Calphad, 54 (2016), pp. 35-53

H. Y. Sohn, Fundamentals of the Kinetics of Heterogeneous Reaction Systems in Extractive Metallurgy .