Hydrogen preserves microstructure to enhance steelmaking dust recycling

- Journal

- Communications Materials

- Year

- 2025

- DOI

- 10.1038/s43246-025-00980-3

Introduction

The global steel industry, a cornerstone of modern infrastructure, is also a major contributor to anthropogenic CO2 emissions, accounting for ~8% of the global total (1.95 Gt of steel produced in 2021)1. A significant portion of this steel is galvanized for corrosion protection, and its recycling in electric arc furnaces (EAFs) is crucial for resource efficiency. However, EAF steelmaking generates substantial quantities of hazardous electric arc furnace dust (EAFD), with a global output of 5.5 to 11 million tons annually (based on 558.4 Mt of EAF steel production and EAFD generation rates of 10–20 kg/ton)2,3. The currently dominant technology for EAFD treatment, the Waelz process, relies on carbothermic reduction, which presents major obstacles to achieving a truly circular economy4,5,6. This process is not only carbon-intensive, requiring ~150 kg of coke7 and emitting nearly 2000 kg of CO2 per ton of recovered zinc, but also achieves only around 90% zinc recovery. Furthermore, it generates 600–650 kg of slag per ton of EAFD8, a byproduct containing residual zinc (2–5%), substantial iron (40–60% as both oxides and metal), and various impurities (SiO2, CaO, MnO, Cr2O3, Cu, Ni, and P)9,10,11. This slag is largely unsuitable for direct recycling because of its high sulfur content and low degree of iron metallization (the fraction of the total iron present as metallic Fe rather than iron oxides) that prevents effective iron recovery and integration back into the EAF, hindering the closed-loop material flow essential for a circular economy12.

Driven by the imperative for industrial decarbonization and a circular economy, hydrogen-based reduction is emerging as a transformative technology for metal recovery13,14,15. Replacing carbon with hydrogen eliminates direct CO2 emissions, a fundamental advantage. Furthermore, hydrogen reduction offers the potential for improved reaction kinetics, leading to more efficient metal extraction16,17. While the basic principles of hydrogen reduction are known, its specific application to complex hazardous waste materials like EAFD, particularly under dynamic, industrially relevant conditions, has not been thoroughly investigated. This study directly addresses this critical gap, providing a comprehensive analysis of hydrogen-based EAFD processing compared to conventional carbothermic methods.

To directly compare hydrogen and carbothermic reduction of EAFD under realistic industrial conditions, we systematically investigated the reduction kinetics of two distinct steelmaking dusts using a dynamic temperature-gas composition profile. This profile mimicked the continuously changing environment a material undergoes within industrial reactors. Our approach combined thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) for kinetic quantification with microstructural and elemental analysis using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with backscattered electron detector (BED) and SEM with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). A key innovation was the transformation of the 2D spatial elemental distribution data into a series of scatter plots, allowing us to identify correlations between elements and infer the presence of specific compounds (e.g., a positive correlation between zinc and sulfur with a 1:1 atomic ratio indicates ZnS). This revealed that CO-based reduction led to denser, less reactive oxide structures, while hydrogen preserved microstructural features conducive to continued reaction. Consequently, hydrogen reduction achieved superior Zn recovery, enhanced iron metallization, and lower residual sulfur and phosphorus. These results demonstrate the clear environmental and process engineering benefits of hydrogen-based EAFD processing, offering a pathway towards more sustainable steelmaking.

Results and discussion

We used TGA to reduce two EAFD samples, comparing hydrogen and carbon-based reduction. The samples differed primarily in their ZnO content (29.6% and 40.7%). The experiments featured a dynamic temperature-gas composition profile, mirroring the changing environment in industrial counter-current reactors. The gas composition was linearly transitioned from a H2O/CO2-rich mixture to pure H2/CO during heating. This allowed direct comparison of H2/H2O and CO/CO2 reduction kinetics under comparable conditions. Post-reduction, SEM-BED imaging enabled phase segmentation (distinguishing porosity, slag, and metal based on brightness) and quantification of macro-porosity and metallization. SEM-EDX mapping provided spatial elemental concentration profiles. Across multiple metrics—including reaction kinetics, microstructure preservation, and impurity removal—hydrogen reduction consistently outperformed carbothermic reduction.

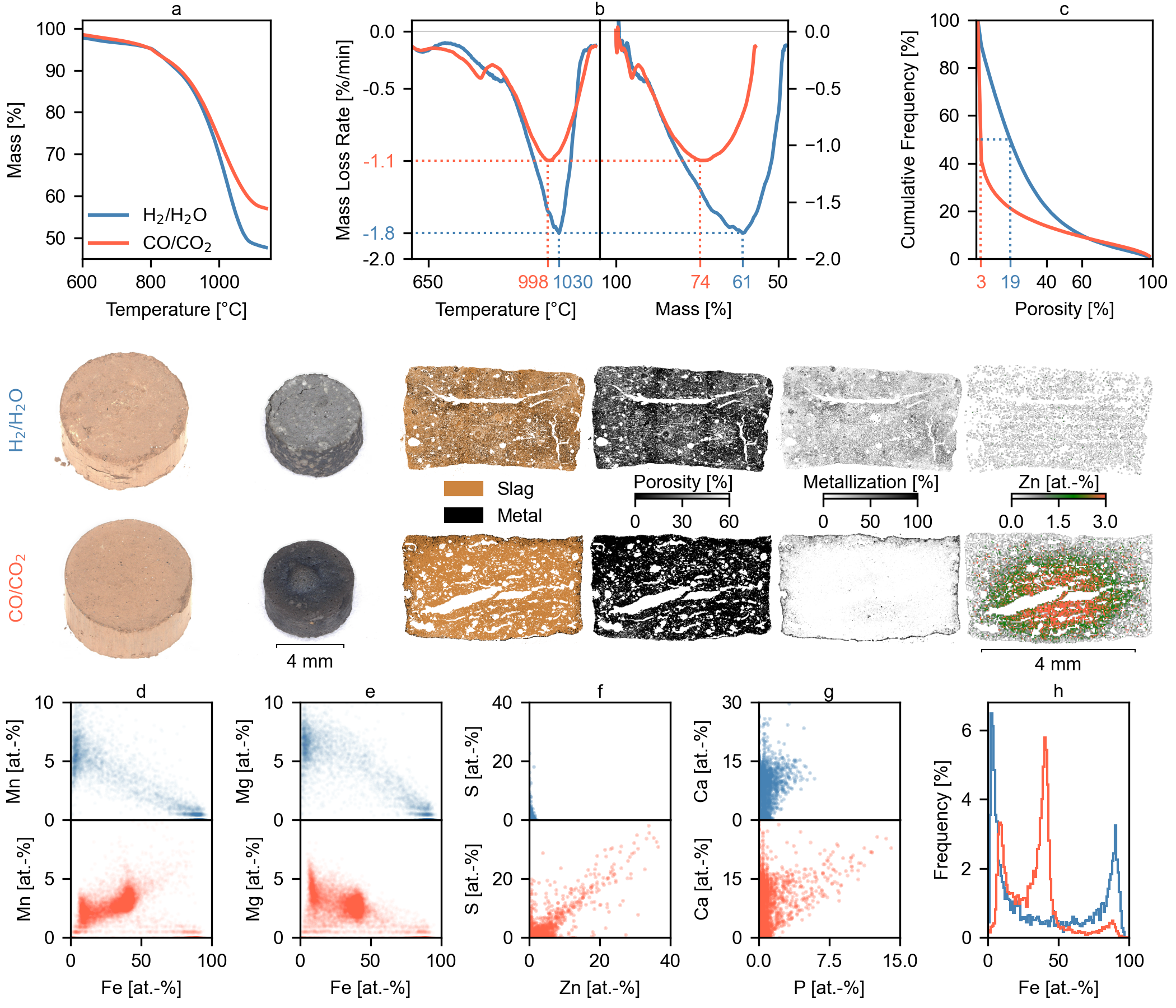

Kinetics and microstructural analysis of EAFD1

Comparing the reduction of EAFD1 in H2/H2O and CO/CO2 atmospheres revealed significant differences in reaction kinetics and microstructural evolution (Fig. 1). The H2/H2O system consistently exhibited superior performance, achieving a higher overall mass loss (Fig. 1a) and greater mass loss rates when compared at equivalent extents of reaction (Fig. 1b). Notably, the maximum reaction rate for the CO/CO2 system occurred at 998 °C with 74% of the sample mass remaining, whereas the peak rate for the H2/H2O system shifted to a higher temperature (1030 °C) and lower residual mass (61%). This difference in the temperature and extent of reaction at the peak rate suggests that, in the CO/CO2 system, reduction kinetics are limited by microstructural changes that occur at elevated temperatures, rather than by the simple depletion of reducible compounds.

SEM-BED imaging, distinguishing phases (void/porosity, slag, and metal) based on brightness differences, confirmed these kinetic differences. Porosity mapping (using 10 × 10 pixel regions, ~9 µm × 9 µm) revealed a significantly larger fraction of low-porosity regions in the CO/CO2-reduced sample. Specifically, 50% of the analyzed area in the CO/CO2 sample exhibited a porosity of 3% or less, whereas only 19% of the analyzed area in the H2/H2O sample had such low porosity. Furthermore, metallization in the H2/H2O system was pervasive and uniformly distributed with a fine particle size distribution, while in the CO/CO2 sample, it was limited to the outer surface, forming a dense contour around the non-metallized matrix. This combination of lower overall porosity and restricted metallization in the CO/CO2 sample directly explains the observed slower reduction kinetics, as gas diffusion to and from reaction sites is hindered.

The CO/CO2 system enters the FeO stability region earlier than H2/H2O and leaves it later (see thermodynamic timeline in thermogravimetric reduction procedure within the materials and methods section). This promotes early densification and dissolution of (Mn, Mg)O into wustite, lowering reaction rates for Fe reduction and Zn fuming. In the H2/H2O system, wustite is stable for a shorter period, limiting (Mn, Mg)O dissolution, preserving pore connectivity, and maintaining internal gas transport. As a result, the system achieves deeper metallization with near-complete Zn removal.

Elemental behavior and impurity removal in EAFD1

SEM-EDX elemental mapping provided further insights into the reduction mechanisms. The CO/CO2 sample displayed a clear Zn concentration gradient (lower at the surface, higher in the center), while the H2/H2O sample showed nearly complete Zn removal. Quantitatively, the Zn concentration decreased from an initial 23.7 wt.-% to 0.1% in the hydrogen system (with 52.3% mass loss), yielding a zinc recovery rate of 99.7%. In contrast, the carbon-based system achieved only 90.0% recovery, with a final Zn concentration of 3.7% (and 43% mass loss)—a value comparable to those obtained in state-of-the-art industrial processes. Turning to the iron behavior, Fe concentration histograms derived from the EDX data (Fig. 1h) confirmed the findings from the SEM-BED images. The CO/CO2 system maintained a stable wüstite region at ~40 at.-% Fe, with evident MnO dissolution into the FeO matrix (Fig. 1d) and a corresponding accumulation of MgO (Fig. 1e). MnO and MgO stabilize the oxide phase, reducing its reactivity and lowering the liquidus temperature, thus promoting earlier sintering and contributing to the observed dense microstructure. In contrast, the H2/H2O sample lacked these correlations and instead exhibited significant metallic Fe formation.

The behavior of sulfur and phosphorus further highlighted the distinct reduction mechanisms in the two atmospheres. In the CO/CO2 sample, sulfur was primarily present as ZnS (Fig. 1f). In contrast, the H2/H2O system lacked this correlation and exhibited a significantly lower bulk sulfur concentration (0.3% vs. 0.8%), likely caused by the formation of H2S. Phosphorus behaved differently: in the CO/CO2 atmosphere, it formed apatite-type phases with calcium (Ca:P ratio of 5:3), while this association was largely absent in the H2/H2O environment, suggesting the formation of volatile phosphorus species (likely PH3). Although final bulk phosphorus concentrations were similar (0.6% vs. 0.7%), the greater mass loss in the H2/H2O system (52.3% vs. 43%) indicates more effective overall phosphorus removal. The lower residual sulfur and phosphorus content in the hydrogen-reduced material significantly benefits its potential for recycling in EAFs, which have limited capabilities for removing these elements. However, process design must account for possible H2S and PH3 formation during hydrogen-based EAFD treatment. Industrial hydrogen operation typically uses gas recirculation with H2O condensation to raise H2 utilization. Because condensation does not remove H2S or PH3, these trace species can accumulate in a closed loop and become hazardous if leaks occur. Upscaling therefore requires on-line H2S/PH3 monitoring in the recycle, with provision for removal by alkaline scrubbing (H2S) and/or solid adsorbents/adsorption–oxidation media (H2S, PH3)18,19.

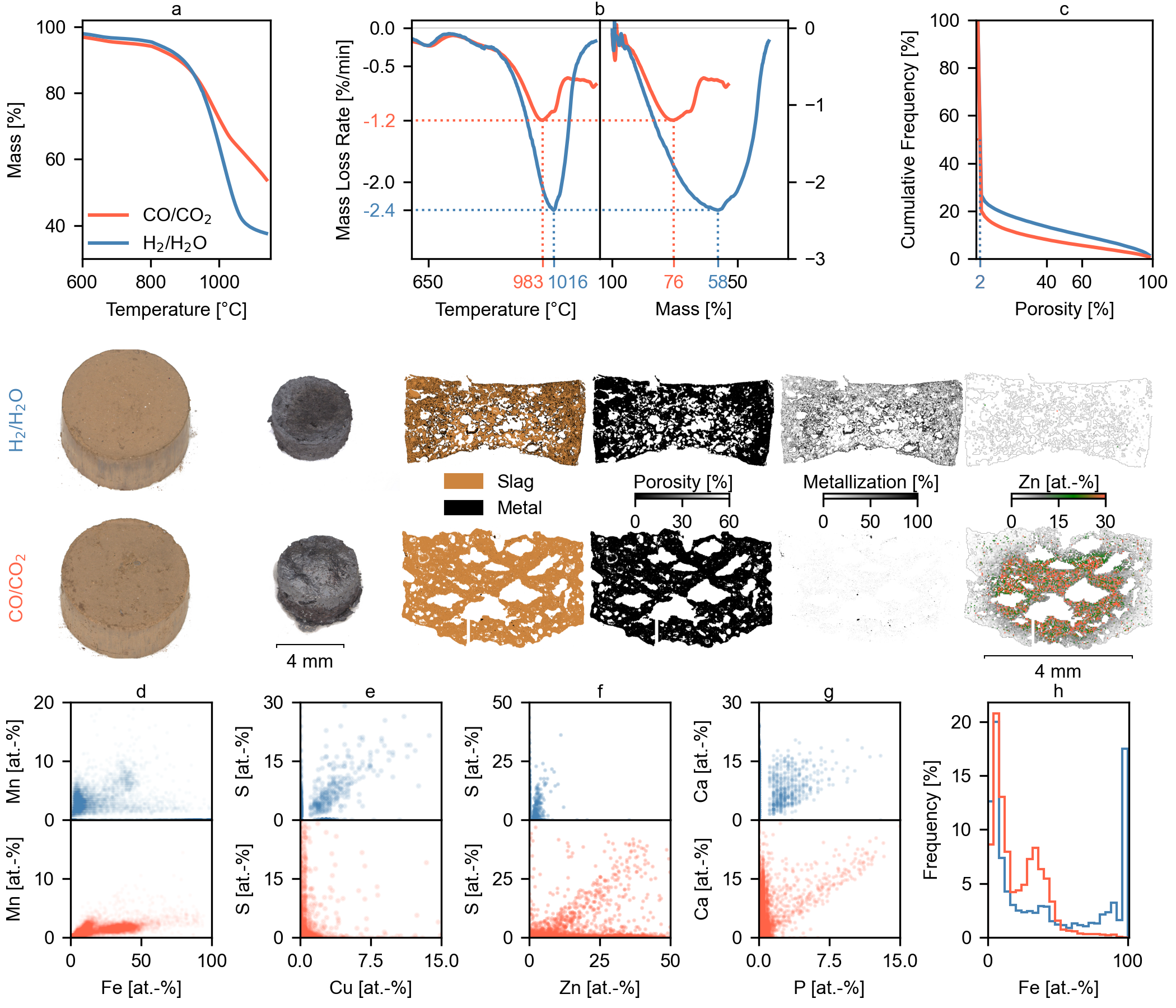

Reduction behavior of high-zinc EAFD2

As with EAFD1, the second dust sample (EAFD2, Fig. 2) showed significantly better reduction performance with H2/H2O compared to CO/CO2. The H2/H2O system achieved a maximum reaction rate of 2.4 mass-%/min, twice that of the CO/CO2 system (1.2%/min). The peak reaction rate occurred at a lower temperature and higher residual mass for CO/CO2 (983 °C, 76% residual mass) than for H2/H2O (1016 °C, 56% residual mass). This difference indicates that while reactant depletion primarily controls the kinetics in the H2/H2O system, pore structure collapse due to sintering limits the reaction progress in the CO/CO2 system. The impact of this sintering-induced pore collapse is observed in both samples earlier in the CO/CO2 system, likely due to the larger size of CO and CO2 molecules compared to H2 and H2O, leading to more significant diffusion limitations as pores shrink.

SEM analysis using the backscatter detector showed that both reduction conditions resulted in dense microstructures with low median porosity (≤2%). However, iron metallization was significantly different: substantial and pervasive in the H2/H2O sample, but minimal in the CO/CO2 sample. Zinc distribution also differed greatly. The CO/CO2 sample showed a steep Zn concentration gradient (surface to core), while the H2 system achieved near-complete Zn removal (1.0% bulk concentration, 98.8% recovery, versus 20.6% and 67.2% for CO/CO2). Examining iron phases, the CO/CO2 sample retained a substantial FeO region with MnO dissolution (Fig. 2d, h). Conversely, the H2/H2O sample consisted mainly of metallic Fe with limited, MnO-enriched FeO. The differences in reduction behavior between EAFD2 and EAFD1 likely stem from the higher initial Zn concentration and longer residence time in the FeO-region in EAFD2. In particular, the higher initial Zn keeps wustite stable for longer even in H2, which initiates densification and Mn/MgO dissolution and thereby lowers the achievable Zn recovery.

Analysis of the elemental correlations, derived from the EDX, revealed a correlation between sulfur and copper under H2 reduction, indicating CuS2 formation (Fig. 2e). A possible explanation is that H2S forms with a higher partial pressure within the dense microstructure, which further reacts with copper. The data also suggest the presence of Fe2S. In contrast, sulfur remained primarily bound to zinc as ZnS in the CO/CO2 sample (Fig. 2f). The bulk sulfur concentrations were 0.9% for the H2 reduction and 1.2% for the CO-based system. After adjusting for the different mass losses, the hydrogen-reduced sample contained 48% less sulfur. Relative to EAFD1, the lower fractional sulfur removal in EAFD2 likely reflects its higher initial sulfur. Sulfur release becomes rate-limited by H2S formation and outward transport, which raises the local H2S partial pressure and promotes secondary sulfide formation. The denser microstructure observed for EAFD2 is consistent with a longer residence in the wustite (FeO) stability region caused by its higher initial zinc which further reinforces this effect. Phosphorus showed a strong correlation with calcium in the CO/CO2 sample (Fig. 2g). This correlation was significantly weaker in the H2/H2O sample, suggesting partial phosphorus removal, likely as volatile PH₃. We hypothesize that the denser microstructure in the H2-reduced sample may have limited PH₃ escape due to restricted diffusion through the collapsed micropore structure.

Summary and conclusion

Hydrogen-based reduction offers a transformative approach to EAFD valorization, significantly outperforming conventional carbothermic methods. Our study, using dynamic temperature-gas profiles to mimic industrial reactor conditions, demonstrates that H2/H2O reduction achieves superior zinc recovery (98.8–99.7% vs. 86.2–90.0% for CO/CO2), enhanced iron metallization, and more effective removal of detrimental elements like sulfur and phosphorus. These improvements stem from hydrogen’s smaller molecular size, higher diffusivity, and greater reactivity, which promote more efficient gas-solid interactions and prevent the sintering-induced pore collapse that hinders reduction in CO/CO2 environments. Importantly, experimental programs should reproduce realistic dwell times within key stability regions (notably wustite), as this is the primary mechanism controlling microstructure evolution, transport, and thus the observed reaction kinetics. Crucially, our findings reveal the potential for selective zinc extraction without iron reduction, opening a pathway for EAFD recycling even before widespread adoption of hydrogen-based ironmaking becomes economically feasible. This work establishes a foundation for optimizing hydrogen-based EAFD processing, contributing to a more sustainable and circular steel industry. Future research should focus on detailed kinetic modeling, the effect of additives on kinetics, selectivity and impurity removal and upscaled validation to assess economic feasibility.

Materials and methods

Two different EAFD materials were used in this study. Material 1 contained 18.8 wt.-% Zn, while Material 2 had a higher Zn concentration of 30.3 wt.-%, measured by X-ray fluorescence (XRF). In both materials, zinc was primarily present as franklinite (ZnFe2O₄) and zinc oxide (ZnO). Iron was present primarily as Fe³⁺ in the form of franklinite and hematite (Fe2O₃). The detailed chemical compositions of the EAFD samples, determined by XRF, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), and SEM-EDX are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Chemical analysis of initial dust samples in wt.-%

Mat | Meth | Zn | Fe | CaO | MgO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | MnO | Cr2O3 | S | Cu | K | Cl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | XRF | 18.8 | 31.0 | 3.52 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 2.96 | 1.02 | 0.4 | 0.40 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

1 | ICP | 19.8 | 31.1 | 6.48 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 3.27 | 1.04 | 0.4 | 0.40 | 0.9 | 2.4 |

1 | EDX | 21.2 | 30.8 | 3.42 | 1.4 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 3.07 | 1.12 | 0.5 | 0.47 | 0.9 | 2.4 |

2 | XRF | 30.3 | 21.0 | 2.46 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 1.43 | 0.55 | 0.6 | 0.35 | 0.6 | 2.0 |

2 | ICP | 30.9 | 19.5 | 4.56 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 1.42 | 0.51 | 0.7 | 0.44 | 1.8 | 5.4 |

2 | EDX | 29.2 | 18.1 | 2.74 | 1.9 | 4.6 | 2.3 | 1.32 | 0.52 | 1.0 | 0.49 | 2.6 | 5.9 |

Sample preparation

EAFD samples were dried at 105 °C for 24 h in a laboratory oven to remove moisture. For each experiment, 350 mg of dried EAFD was compacted using a custom-designed electromechanical uniaxial press at 14 MPa. The resulting cylindrical specimens had a diameter of 7.5 mm and a height of 3.75 mm, yielding a geometric surface area of 176.7 mm² and a bulk density of 2.1 g/cm³. These dimensions resulted in uniform gas diffusion paths of ≤3.75 mm through the sample’s macroporous structure. Sample morphology and exact dimensions were documented using a Keyence VHX-7000 digital microscope prior to reduction experiments.

Thermogravimetric reduction procedure

Reduction experiments were conducted in a customized Linseis STA PT 1600, as described in detail by Brandner et al.20. Temperature control was achieved using a type C (tungsten-rhenium) thermocouple integrated into the sample holder. The TGA was configured to simulate the conditions experienced by material in a counter-current reactor, where the temperature increases and the gas composition transitions from oxidizing (H2O/CO2-rich) to reducing (H2/CO-rich). It is important to note that while the volumetric gas flow rates of CO/CO2 and H2/H2O were the same, the different molar masses and reaction stoichiometries result in different thermodynamic equilibria.

The experimental profile (Fig. 3a) consisted of three zones: a drying zone (up to 200 °C), a heating zone with constant gas composition (up to 800 °C), and a reduction zone with a continuously changing gas composition. Samples were heated to 300 °C at 25 K/min in a 61% H2O and 39% H2 atmosphere, followed by heating rates of 20 K/min to 500 °C and 12.5 K/min to 800 °C. From 800 °C to 1150 °C, the temperature increased at 5.83 K/min over 1 h. During this final heating segment, the H2O/CO2 flow rate decreased linearly from 50 ml/min to 0 ml/min, while the H2/CO flow rate increased linearly from 30 ml/min to 80 ml/min. Consequently, the inflowing gas consisted of 100% H2/CO once the sample reached 1150 °C. Samples were subsequently cooled at 25 K/min under an inert argon atmosphere.

The thermodynamic conditions for the H2 system (Fig. 3b) indicate that wüstite (FeO) becomes stable at ~800 °C. The reduction of ZnO to gaseous Zn depends on the partial pressure of Zn(g); at a partial pressure of 0.01 bar, Zn(g) becomes thermodynamically stable at around 900 °C, corresponding to the onset of significant zinc fuming observed in the TGA. Conditions favorable for FeO reduction to Fe occur at ~940 °C. In the CO system (Fig. 3c), wüstite becomes stable earlier (at around 740 °C), Zn(g) fuming (at 0.01 bar) begins at around 910 °C, and FeO reduction starts at ~990 °C. Therefore, from a purely thermodynamic perspective, the sample in the CO system resides in the wüstite stability region for at least 37 min, compared to 24 min for the H2 system.

SEM-based analysis

Samples were characterized after reduction using a JEOL IT300 scanning electron microscope. Backscatter images were acquired with a pixel step size of 0.9 µm per pixel, while EDX mappings (Oxford X-Max50 EDX Detector) used a step size of 29.3 µm per pixel with at least 6000 counts per pixel. The acceleration voltage was 20 kV with a working distance of 10 mm. Quantification of EDX mappings was performed using Aztec 6.0 SP2 with the Extended Set of Quant Standardizations. EDX maps were exported as 16-bit TIFF files, and metadata including stage position, count statistics, and BED data were exported using the HDF5 export feature of Aztec. Further evaluation of the data, including image stitching and cluster analysis, was performed using Python. Porosity and metallization distributions were derived from the backscattered-electron images by computing local area-fraction porosity and metallization in non-overlapping 10 × 10-pixel windows (≈9 × 9 µm at 0.9 µm px⁻¹) after brightness-based segmentation of the BED greyscale.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Manuel Leuchtenmüller (manuel.leuchtenmueller@unileoben.ac.at), upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The custom code used for data analysis in this study is available from the author upon request.

References

Zhang, Y., Yu, L., Cui, K., Wang, H. & Fu, T. Carbon capture and storage technology by steel-making slags: recent progress and future challenges. Chem. Eng. J. 455, 140552 (2023).

Hundt, C. & Pothen, F. European post-consumer steel scrap in 2050: a review of estimates and modeling assumptions. Recycling 10, 21 (2025).

Guézennec, A.-G. et al. Dust formation in electric arc furnace: birth of the particles. Powder Technol. 157, 2–11 (2005).

Mager, K. et al. Recovery of zinc oxide from secondary raw materials: new developments of the Waelz process. In Recycling of Metals and Engineered Materials (eds Stewart, D. L., Daley, J. C. & Stephens, R. L.) 329–344 (John Wiley. & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118788073.ch29.

Antrekowitsch, J., Rösler, G. & Steinacker, S. State of the art in steel mill dust recycling. Chem. Ing. Tech. 87, 1498–1503 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Pyrometallurgical recovery of zinc and valuable metals from electric arc furnace dust – a review. J. Clean. Prod. 298, 126788 (2021).

Ruh, A. & Kim, D.-S. The Waelz process - worldwide most used process for the recycling of zinc containing residues. In Proc. European Metallurgical Conference GDMB Verlag GmbH (Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany).

Grudinsky, P. I., Zinoveev, D. V., Dyubanov, V. G. & Kozlov, P. A. State of the art and prospect for recycling of Waelz Slag from electric arc furnace dust processing. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 10, 1220–1226 (2019).

Barna, R. et al. Assessment of chemical sensitivity of Waelz slag. Waste Manag. 20, 115–124 (2000).

Cifrian, E., Coronado, M., Quijorna, N., Alonso-Santurde, R. & Andrés, A. Waelz slag-based construction ceramics: effect of the trial scale on technological and environmental properties. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 18, 763 (2019).

Mombelli, D., Mapelli, C., Barella, S., Gruttadauria, A. & Di Landro, U. Laboratory investigation of Waelz slag stabilization. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 94, 227–238 (2015).

Maczek, H. & Kola, R. Recovery of zinc and lead from electric-furnace steelmaking dust at Berzelius. JOM 32, 53–58 (1980).

Brandner, U., Antrekowitsch, J. & Leuchtenmueller, M. A review on the fundamentals of hydrogen-based reduction and recycling concepts for electric arc furnace dust extended by a novel conceptualization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 46, 31894–31902 (2021).

Guggilam C. S. Recycling of Electric Arc Furnace Dust. https://patents.google.com/patent/DE102023117072A1/en?oq=DE102023117072A1 (ITT Research Institute, 1990).

Palzer, P. & Hand Köhne, S. Method For Processing A Residue Mixture Containing The Elements Iron And/Or Calcium, And Corresponding Processing Plant.

Brandner, U. & Leuchtenmueller, M. Comparison of reduction kinetics of Fe2O3, ZnOFe2O3 and ZnO with hydrogen (H2) and carbon monoxide (CO). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 49, 775–785 (2024).

Leuchtenmüller, M. & Keuschnig, A. Impact of temperature and gas composition on hydrogen-based zinc recovery from electric arc furnace dust. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 130, 434–439 (2025).

Tang, Y. et al. Low-temperature efficient removal of PH3 over novel Cu-based adsorbent in an anaerobic environment. Chem. Eng. J. 461, 142078 (2023).

Pudi, A. et al. Hydrogen sulfide capture and removal technologies: a comprehensive review of recent developments and emerging trends. Sep. Purif. Technol. 298, 121448 (2022).

Brandner, U., Antrekowitsch, J., Hoffelner, F. & Leuchtenmueller, M. A Tailor-made experimental setup for thermogravimetric analysis of the hydrogen- and carbon monoxide-based reduction of iron (III) oxide (Fe2O3) and zinc ferrite (ZnOFe2O3). In TMS 2022 151st Annual Meeting & Exhibition Supplemental Proceedings (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022) 917–926.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe program under Grant Agreement No. 101138742. The author thanks Eleonora Shpilevaia and Aaron Keuschnig for their assistance with the experimental work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Nonferrous Metallurgy, Montanuniversitaet Leoben, Leoben, Austria

Manuel Leuchtenmüller

Contributions

Manuel Leuchtenmüller designed the study, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Manuel Leuchtenmüller.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During manuscript preparation, I used Google Gemini/ChatGPT to refine phrasing; I reviewed all content and take full responsibility.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Siwei Li and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.