Impact of temperature and gas composition on hydrogen-based zinc recovery from electric arc furnace dust

- Journal

- International Journal of Hydrogen Energy

- Year

- 2025

- DOI

- 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.04.366

Introduction

Galvanizing steel products accounts for 60 % of global zinc production and remains zinc's primary industrial application, owing to its good corrosion protection properties [1]. However, recycling galvanized steel scrap—a critical step toward promoting circular resource use—produces hazardous waste streams, such as electric arc furnace dust (EAFD) and converter dust [2,3]. These dusts are produced at rates of 15–25 kg per ton of steel in electric arc furnace (EAF) operations [4,5]. They contain valuable amounts of zinc (Zn), with concentrations reaching up to 40 %, depending on the composition of the recycled scrap and the operating conditions of the furnace [6,7]. Currently, Waelz kilns primarily treat these dusts. While they effectively recover Zn, they do not recover the substantial iron content [8]. Although the Waelz process achieves high zinc recovery rates, it generates approximately 700 kg of slag per ton of treated EAFD. This slag contains 30–50 % Fe as Fe oxide and 1–4 % residual Zn [9,10]. Depending on regional regulations and the specific parameters of the Waelz process, slag may be repurposed as construction material or disposed of in landfills, leading to a loss of valuables. Moreover, the process's carbothermic reduction pathway results in substantial CO2 emissions, exceeding 2000 kg per ton of Zn recovered [11].

To address the environmental challenges associated with the Waelz process, hydrogen-based direct reduction has emerged as a promising low-carbon alternative. Unlike carbothermic methods, hydrogen reduction eliminates carbon emissions from the reduction reaction, providing a pathway to decarbonize Zn recovery. Recent industrial efforts have explored hydrogen-based direct reduction technologies, including rotary kiln designs developed by Salzgitter and batch-process systems utilizing pressurized reactors, as researched by GreenIron and documented in multiple patents over recent years [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15]]. However, the implementation of hydrogen-based reduction technologies remains in its infancy, facing numerous technical challenges that need to be addressed.

A key challenge in hydrogen-based reduction is the optimization of reaction conditions, particularly temperature, to maximize Zn recovery efficiency. Reduction temperature influences reaction kinetics, microstructural changes, and the sintering behavior of dust particles. Although detailed kinetic studies have been conducted on the hydrogen-based reduction of zinc oxide (ZnO) from liquid slags [[16], [17], [18]], research on the solid-state direct reduction of Zn and Fe oxides in electric arc furnace dust (EAFD) is limited. Most recent publications concentrate on broader hydrogen-based steelmaking processes or specific case studies, often neglecting the underlying kinetic mechanisms and optimal operating conditions necessary for efficient Zn recovery [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23]]. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation into the temperature-dependent behavior of EAFD during hydrogen reduction is essential to bridge this knowledge gap.

This study investigates how temperature and gas composition control the reduction behavior of electric arc furnace dust (EAFD) during hydrogen-based processing. We examine the effects of reduction temperature (900–1200 °C) and H2 and H2O composition on reaction kinetics and microstructural evolution. Through thermogravimetric analysis and subsequent material characterization, we establish quantitative relationships between reduction conditions and Zn recovery efficiency. These insights establish fundamental principles and practical guidelines for the process engineering of efficient hydrogen-based recovery of EAFD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Dust material

The electric arc furnace dust (EAFD) investigated in this study was provided by Georgsmarienhütte GmbH (Germany). Physical characterization revealed a trimodal particle size distribution, determined by laser diffraction analysis, with D10 = 0.30 μm, D50 = 1.3 μm, and D99 = 20.0 μm. The specific surface area, measured using N2 adsorption (Micromeritics TriStar II 3020) following the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method, was 8.4 m2/g.

The chemical composition was determined through complementary analytical techniques: X-ray fluorescence (XRF) for major elements, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) for trace elements, and scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) for composition analysis. Table 1 summarizes the chemical composition data. Mineralogy was determined using X-ray Diffraction (XRD) by means of a Rigaku SmartLab SE diffractometer in θ-θ configuration (Cu-Kα radiation: λ = 1.54 Å at 40 kV. 40 mA) to evaluate the mineralogy of the samples. It revealed that the main phases in the material are franklinte, zincite and halite (NaCl).

Table 1. Analysis of the investigated EAFD.

XRF (wt.-%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ZnO | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | MnO | Cr2O3 |

26.2 | 44.3 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

K2O | Na2O | Cl | PbO | CuO | P2O5 | S | Ctot. |

0.6 | 4.6 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2.0 |

ICP-MS (wt.-%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Co % | Hg % | Cd % | Sn % | P % | Mo % |

<0.02 | <0.01 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.05 | <0.02 |

2.2. Sample preparation

EAFD samples were dried at 105 °C for 24 h in a laboratory oven to remove moisture. For each experiment, 350 mg of dried EAFD was compacted using a custom-designed electromechanical press at 14 MPa. The specimens were pressed to final dimensions of 7.5 mm diameter and 3.75 mm height, yielding a geometric surface area of 176.7 mm2 and a bulk density of 2.1 g/cm3. These dimensions ensured uniform gas diffusion paths ≤3.75 mm through the sample's macroporous structure, minimizing mass transport limitations during reduction experiments. Sample morphology and exact dimensions were documented using digital microscopy Keyence VHX-7000 prior to reduction experiments.

2.3. Thermogravimetric reduction procedure

Reduction experiments were conducted in a customized Linseis thermogravimetric analyzer, previously described in detail by Brandner et al. [24]. Temperature control was achieved using a type C thermocouple integrated into the sample holder. Samples were heated at 25 K/min to 200 °C, followed by 40 K/min heating in nitrogen (5.0 grade, 80 mL/min) until reaching the target temperature. After 15 min of temperature homogenization, the atmosphere was switched to hydrogen (3.0 grade, 80 mL/min) for the 120-min reduction period. Samples were subsequently cooled at 25 K/min under inert conditions.2.3. Thermogravimetric reduction procedure

Reduction experiments were conducted in a customized Linseis thermogravimetric analyzer, previously described in detail by Brandner et al. [24]. Temperature control was achieved using a type C thermocouple integrated into the sample holder. Samples were heated at 25 K/min to 200 °C, followed by 40 K/min heating in nitrogen (5.0 grade, 80 mL/min) until reaching the target temperature. After 15 min of temperature homogenization, the atmosphere was switched to hydrogen (3.0 grade, 80 mL/min) for the 120-min reduction period. Samples were subsequently cooled at 25 K/min under inert conditions.

2.4. Reaction thermodynamics and kinetic analysis

The primary reduction reactions and their Gibbs free energy changes (Table 2) were calculated using FactSage thermochemical software. Reaction kinetics were evaluated through numerical differentiation of the continuous mass loss data with respect to time, providing instantaneous reaction rates throughout the reduction process.

2.5. Post-reduction sample analysis

Reduced samples were characterized dimensionally using a Keyence VHX-7000 digital microscope. Microstructural analysis was performed using a JEOL IT300 SEM equipped with an Oxford X-Max50 EDX detector. Selected samples were prepared metallographically through resin embedding, grinding, and polishing for cross-sectional analysis.

3. Results and discussion

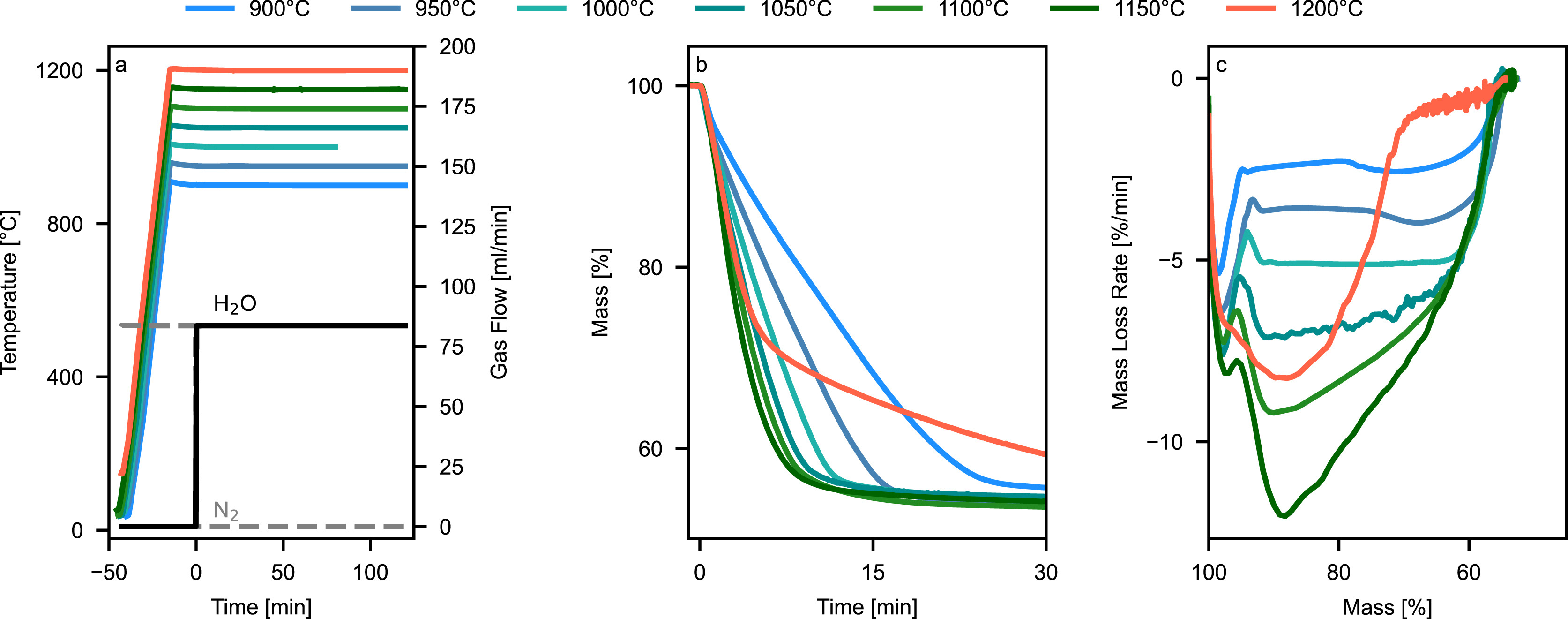

The thermogravimetric analysis revealed distinct temperature-dependent reduction behavior of EAFD between 900 and 1200 °C (Fig. 1). The reduction proceeds through a moving reaction front, characterized by three mechanistic regimes: surface-controlled kinetics from 900 to around 1100 °C where thermodynamics limit the kinetics of ZnO reduction, an optimal reduction window at around 1150 °C, and solid-state diffusion-limited regime beginning between 1150 and 1200 °C.

The reduction of EAFD proceeds through multiple simultaneous reactions, each limited by thermodynamic requirements especially regarding the H2/H2O ratio (Table 3). These requirements change with temperature, creating distinct reaction patterns at different process conditions. As H2 gas penetrates from the sample surface inward, all reduction reactions progress concentrically and top down. The reaction of Fe2O3 to Fe3O4 occurs readily throughout the accessible sample volume due to its minimal H2/H2O requirement (<0.01). At 900 °C, subsequent reduction steps establish reaction zones of decreasing depth: The Fe3O4 to FeO conversion (H2/H2O > 0.4) forms the deepest reaction front, enabling reduction across a substantial sample volume. The FeO to Fe reduction zone (H2/H2O > 1.3) follows with a narrower reaction front and consequently smaller active reaction volume. ZnO reduction, requiring the highest H2/H2O ratio (>12.6 at pZn = 0.1 bar), establishes the most restricted reaction front width, resulting in the smallest active reaction volume and thus limiting the overall zinc removal rate despite occurring simultaneously with the iron oxide reductions.

Table 3. Minimum required ratio between H2 to H2O to reach thermodynamic equilibrium (ΔG = 0).

Reduction Reaction | Required H2/H2O at | |

|---|---|---|

900 °C | 1200 °C | |

3Fe2O3 + H2 2Fe3O4 + H2O | <0.01 | <0.01 |

Fe3O4 + H2 3FeO + H2O | 0.4 | 0.1 |

FeO + H2 Fe + H2O | 1.8 | 1.3 |

ZnO + H2 Zn(g)a + H2O | 12.6 | 0.1 |

a Assuming Zn partial pressure of 0.1 bar.

Increasing the temperature from 900 °C to 1200 °C fundamentally transforms the reaction front architecture. While Fe2O3 reduction maintains its presence throughout the accessible sample volume, the required H2/H2O ratio for ZnO reduction drops remarkably to 0.1 for a pZn of 0.1 bar - matching the thermodynamic conditions for Fe3O4 to FeO conversion. This enables ZnO and Fe3O4 reductions to proceed with similarly deep reaction fronts, creating an expanded reaction volume for zinc removal. Only the final FeO to Fe conversion (H2/H2O > 1.8) forms a more confined reaction zone. The significantly larger reaction volume for ZnO reduction, combined with its higher molecular mass loss (81 g/mol compared to 16 g/mol for iron oxide steps), substantially accelerates the detected mass loss rate at higher temperature. This synergy between expanded reaction volume and higher mass loss per mole particularly enhances zinc removal rates at elevated temperatures.

While higher temperatures initially benefit the process through expanded reaction zones and improved conversion rates, sintering effects between 1150 and 1200 °C establish a critical upper temperature limit. The collapse of the EAFD's microporous structure begins immediately at 1200 °C but intensifies during wüstite formation, as it has the lowest melting and sintering temperature of all iron oxides. This structural degradation shifts the rate-limiting mechanism from gas-phase diffusion through the macro and micropore structure of the sample to solid-state diffusion. The micropore collapse in the wüstite region marks a critical point where the mass loss rate at 1200 °C falls significantly below the 900 °C trial, demonstrating the dominance of diffusional limitations over thermodynamic advantages.

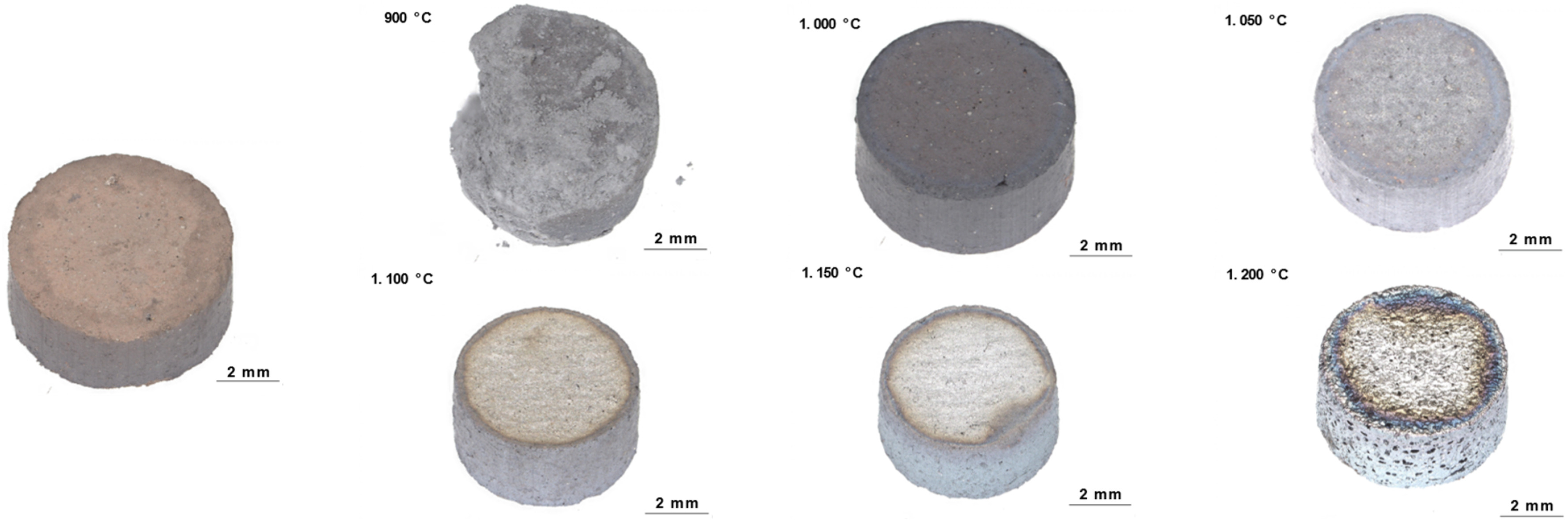

The visual appearance and structural integrity of reduced samples varied markedly across the temperature range studied (Fig. 2). Samples reduced between 900 and 950 °C exhibited a fine-grained texture without signs of sintering, characterized by increased fragility indicating enhanced specific surface area. Despite their distinctly different optical appearance from samples treated at higher temperatures (1100–1200 °C), the mass loss during reduction was similar, suggesting comparable metallization degrees. As reduction temperature increased to 1000 °C, samples developed improved structural integrity with characteristic black coloration, attributed to fine-grained metallic iron particles potentially interspersed with residual oxides. At 1050 °C, distinct metallic surface characteristics emerged, due to increased sintering and densification. Samples reduced at 1100 °C and 1150 °C showed similar features with slightly enhanced surface densification, corresponding to peak reduction rates. A major morphological transformation occurred at 1200 °C, where samples developed a distinctive glittering surface appearance, indicating extensive micropore collapse to a macropore structure.

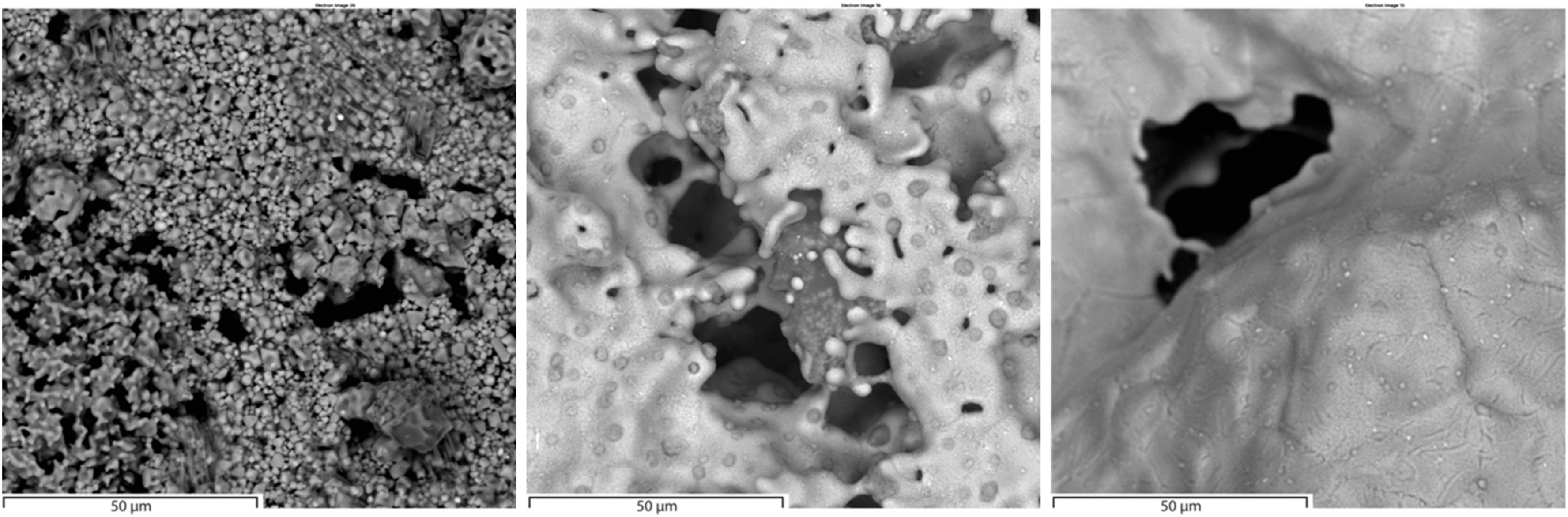

Microstructural evolution was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with secondary electron detection (SED), providing direct evidence of temperature-dependent structural changes (Fig. 3). At 1100 °C, the microstructure consisted of fine-grained particles with a highly porous network of interconnected micropores, indicating minimal sintering and enabling efficient gas diffusion pathways - consistent with the sustained reaction rates observed in TGA data. SEM-EDX analysis was performed on this reduced sample and revealed a ZnO concentration of 0.2 %. A significant transition occurred at 1150 °C, where pronounced sintering led to a denser, more compact structure through the coalescence of iron monoxide (FeO) and metallic iron (Fe) phases. This partial collapse of micropores reduced available gas diffusion pathways, correlating with declining mass loss rates in later reduction stages. Notably, extended reduction durations at this temperature significantly impair sample kinetics, though this effect remains undetected in our short-duration reduction experiments using small samples with gas diffusion paths limited to 3.75 mm. The most dramatic transformation appeared at 1200 °C, where the microstructure revealed complete micropore collapse, leaving only macropores in an otherwise fully dense material. This structural densification confirms the transition to a solid-state diffusion-limited regime, explaining the steep decline in reaction rates despite more favorable thermodynamics at this temperature. The progressive

icrostructural evolution, particularly evident between 1100 °C and 1200 °C, directly aligns with TGA findings and emphasizes the critical role of sintering dynamics in limiting reduction efficiency at elevated temperatures. Notably, 1150 °C emerges as a threshold temperature, balancing optimal reduction kinetics with structural integrity before excessive densification impedes gas transport.

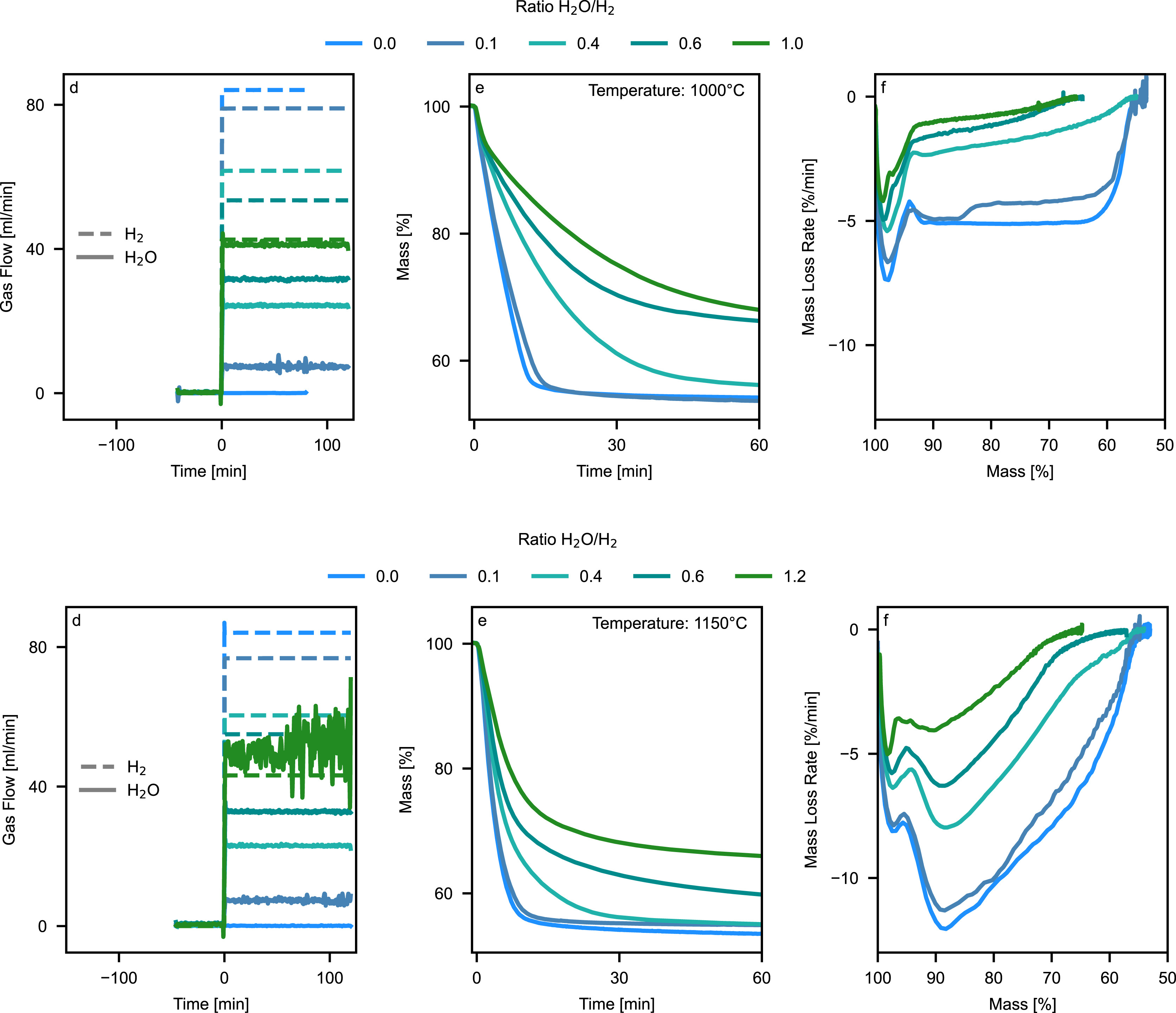

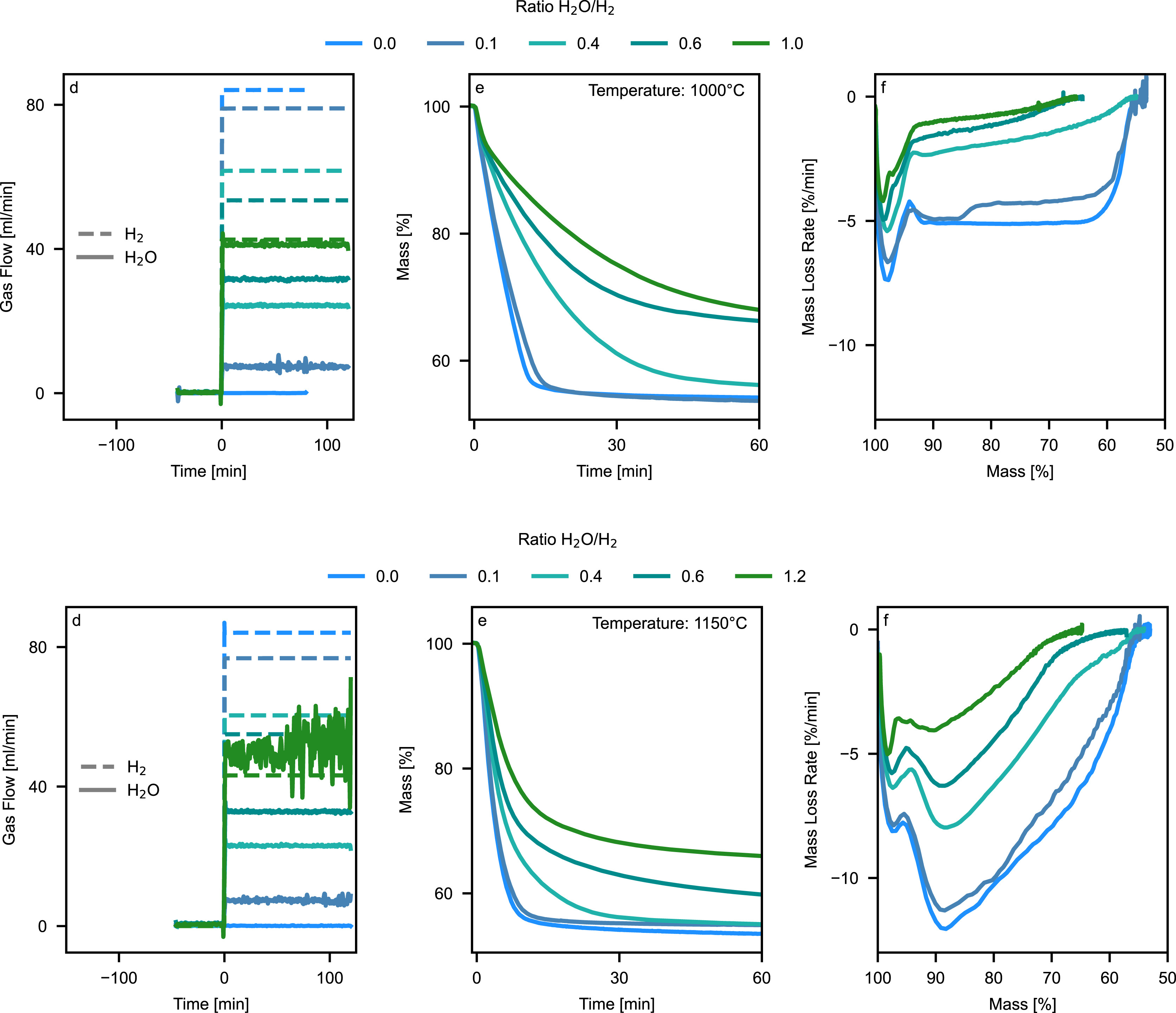

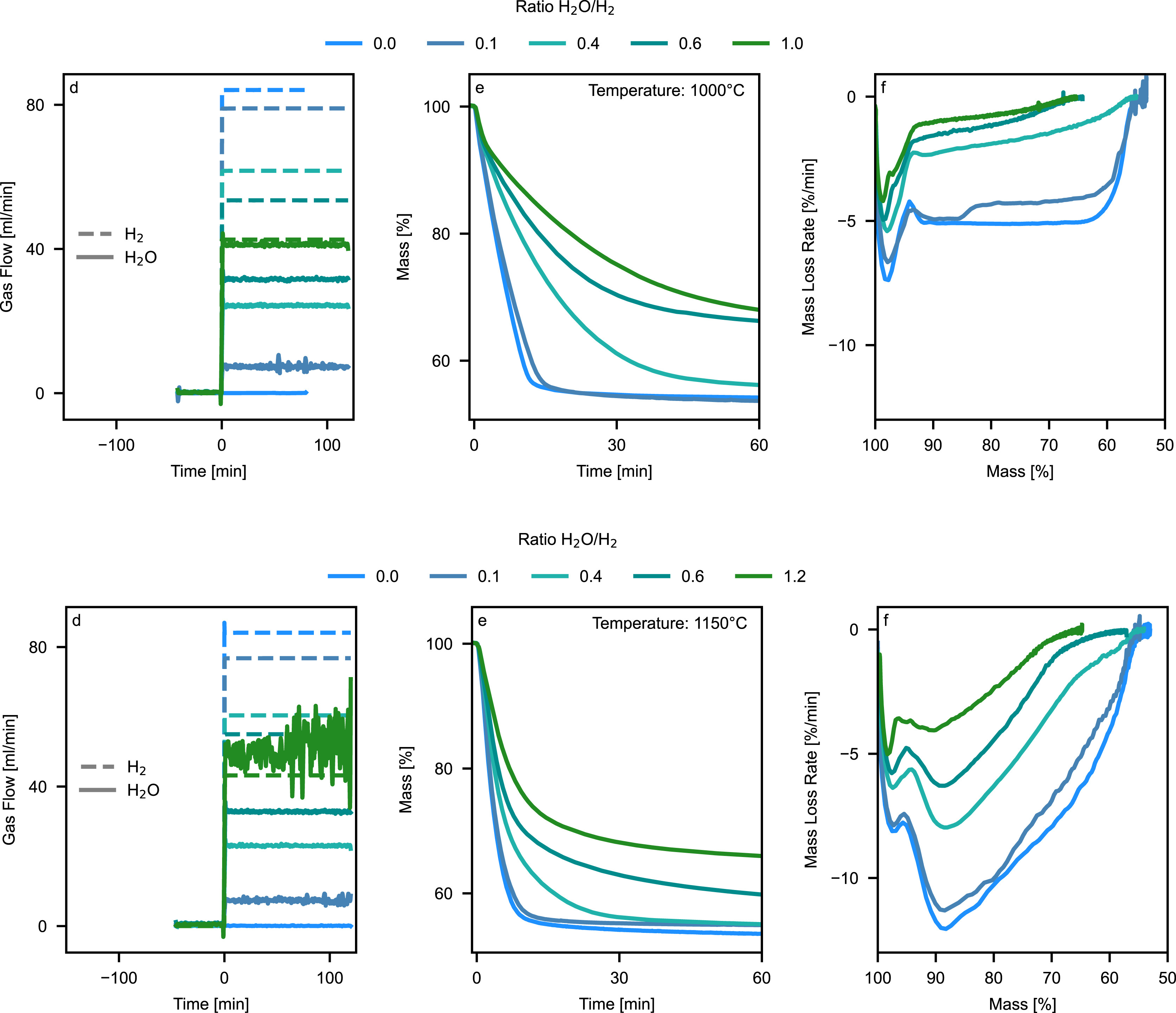

Gas atmosphere composition, particularly the H2O/H2 ratio, significantly influences reduction kinetics alongside temperature. Thermogravimetric experiments at 1000 °C and 1150 °C, using systematically varied H2O/H2 ratios between 0 and 1.2, revealed temperature-specific mass loss patterns and reaction kinetics (Fig. 4). Two gas-related mechanisms control the reduction rates: First, H2 concentration at reaction sites determines collision frequency between H2 molecules and metal oxides, directly affecting reaction probability. Second, the rate of H2O removal from reaction zones influences local thermodynamic conditions. Reaction front formation under elevated bulk H2O concentrations reduces the H2O diffusion gradient from sample to gas phase. The resulting H2O accumulation at reaction sites decreases local thermodynamic driving forces, limiting reaction front penetration depth and kinetically active sample volume, thus reducing overall reaction rates.

At 1000 °C, mass loss profiles initially show rapid reduction of Fe2O3 to Fe3O4 and ZnFe2O4 decomposition to ZnO and Fe3O4. For H2O/H2 ratios up to 0.1, subsequent reduction proceeds with stable rates throughout the sample volume, indicating chemical reaction control rather than macropore diffusion limitations. As H2O/H2 ratios increase to 0.4, mass loss rates progressively decrease while maintaining the achievable reduction degree, suggesting the formation of reaction fronts with reduced kinetically active volume due to H2O accumulation in the sample pores. Above H2O/H2 ratios of 0.6, overall mass loss decreases, indicating thermodynamic limitations that prevent complete FeO to Fe conversion.

At 1150 °C, the reaction pattern changes fundamentally. After initial Fe2O3 and ZnFe2O4 reduction, a second distinct rate maximum appears at approximately 90 % relative mass, corresponding to accelerated ZnO reduction at higher temperatures. The subsequent continuous rate decrease reflects a shrinking reaction front moving inward from the sample surface, with reaction kinetics controlled by the decreasing active surface area. While the final reduction degrees remain the same for H2O/H2 ratios up to 0.6 at both temperatures, the experiment at H2O/H2 = 1.2 at 1150 °C shows decreased mass loss due to thermodynamic limitations for Fe metallization.

4. Conclusion

This study provides fundamental mechanistic insights into the temperature-dependent reduction behavior of electric arc furnace dust (EAFD) during hydrogen-based direct reduction. A key contribution is the identification and mechanistic explanation of a critical temperature threshold (∼1150 °C) that dictates process viability. While kinetics are significantly enhanced below this threshold (up to five-fold increase compared to 900 °C), we demonstrate that exceeding it triggers rapid micropore collapse due to sintering, particularly in FeO-rich regions. This shifts the process to a diffusion-limited regime, drastically impairing reduction efficiency despite favorable thermodynamics. Furthermore, we elucidated the detrimental, self-limiting role of reaction-generated H2O, which imposes local thermodynamic barriers and promotes structural degradation via sintering, further constraining the optimal operating window.

These mechanistic insights directly explain operational challenges potentially encountered in high-temperature reduction processes and underscore why precise temperature control is paramount. Establishing the existence and cause of this upper temperature limit is a critical contribution for future process design, setting a maximum operating temperature to maintain structural integrity and high reaction rates. Identifying these limitations also highlights key areas for future research, including the impact of EAFD compositional variations, the potential of structural stabilizers (e.g., CaO) to extend the operating window, scale-up considerations, and practical temperature control strategies.

Ultimately, this fundamental understanding of the coupled kinetics, thermodynamics, and microstructural evolution advances the development of hydrogen-based reduction technologies. By defining the critical parameters and operational boundaries governing EAFD reduction, this work provides essential knowledge supporting efficient Zn and Fe recovery, contributing to steel industry decarbonization efforts and promoting circular resource utilization.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Manuel Leuchtenmüller: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Aaron Keuschnig: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the European Union's Horizon Europe program under Grant Agreement No. 101138742.

References

Natural Resources Canada, “Zinc Facts,” https://natural-resources.canada.ca/our-natural-resources/minerals-mining/mining-data-statistics-and-analysis/minerals-metals-facts/zinc-facts/20534.

Mark Atkinson, Robert Kolarik

Steel industry technology roadmap

AISI (2001)

J.G.M.S. Machado, F.A. Brehm, C.A.M. Moraes, et al.

Chemical, physical, structural and morphological characterization of the electric arc furnace dust

J Hazard Mater, 136 (3) (2006), pp. 953-960

A.-G. Guézennec, J.-C. Huber, F. Patisson, et al.

Dust formation in electric arc furnace: birth of the particles

Powder Technol, 157 (1–3) (2005), pp. 2-11

C. Lanzerstorfer

Electric arc furnace (EAF) dust: application of air classification for improved zinc enrichment in in-plant recycling

J Clean Prod, 174 (2018), pp. 1-6

T. Suetens, B. Klaasen, K. van Acker, et al.

Comparison of electric arc furnace dust treatment technologies using exergy efficiency

J Clean Prod, 65 (2014), pp. 152-167

R.L. Nyirenda

The processing of steelmaking flue-dust: a review

Miner Eng, 4 (7–11) (1991), pp. 1003-1025

European Commission - JRC Directorate B: Growth and Innovation - European IPPC Bureau

Best available techniques (BAT) reference document for the non-ferrous metals industries: industrial Emissions Directive 2010/75/EU (integrated pollution prevention and control)

Publications Office, Luxembourg (2017)

P.I. Grudinsky, D.V. Zinoveev, V.G. Dyubanov, et al.

State of the art and prospect for recycling of Waelz slag from electric arc furnace dust processing

Inorg Mater: Appl Res, 10 (5) (2019), pp. 1220-1226

R. Barna, H.-R. Bae, J. Méhu, et al.

Assessment of chemical sensitivity of Waelz slag

Waste Manag, 20 (2–3) (2000), pp. 115-124

H. Murray

Method and device for producing direct reduced metal: SE 2050356 A1

(2020)

H. Murray

Method and device for producing direct reduced metal: pct/SE2020/050335

(2022)

H. Murray

Method and device for producing direct reduced metal: pct/SE2020/050336

(2022)

H. Murray

Method and device for producing direct reduced metal: pct/SE2023/050486

(2023)

P. Palzer

Method for processlng a residue mixture contalning the elements lron and/or calcium, and corresponding processlng plant

(2025)

M. Leuchtenmueller, C. Legerer, U. Brandner, et al.

Carbothermic reduction of zinc containing industrial wastes: a kinetic model

Metall Mater Trans B, 52 (1) (2021), pp. 548-557

M. Leuchtenmueller, W. Schatzmann, S. Steinlechner

A kinetic study to recover valuables from hazardous ISF slag

J Environ Chem Eng, 8 (4) (2020), Article 103976

M. Leuchtenmüller, U. Brandner

The catalytic effect of the metal bath on the zinc oxide reduction

Results Eng, 16 (2022), Article 100514

U. Brandner, J. Antrekowitsch, M. Leuchtenmueller

A review on the fundamentals of hydrogen-based reduction and recycling concepts for electric arc furnace dust extended by a novel conceptualization

Int J Hydrogen Energy, 46 (62) (2021), pp. 31894-31902

U. Brandner, M. Leuchtenmueller

Comparison of reduction kinetics of Fe2O3, ZnOFe2O3 and ZnO with hydrogen (H2) and carbon monoxide (CO)

Int J Hydrogen Energy, 49 (2024), pp. 775-785

X. Huo, D. Wang, J. Yang, et al.

Efficient reduction of electric arc furnace dust by CO/H2 derived from waste biomass: biomass gasification, zinc removal kinetics and mechanism

Waste Management (New York, N.Y.), 193 (2024), pp. 44-53

O. Marzoughi, L. Tafaghodi

Hydrogen as a sustainable reducing agent for recycling electric arc furnace dust: a kinetic review

J Sustain Metallurgy, 11 (2024), pp. 232-247

O. Kovtun, M. Levchenko, S. Höntsch, et al.

Recycling of iron-rich basic oxygen furnace dust using hydrogen-based direct reduction

Resources Conservation Recycling Adv, 23 (2024), Article 200225

U. Brandner, J. Antrekowitsch, F. Hoffelner, et al.

A tailor-made experimental setup for thermogravimetric analysis of the hydrogen- and carbon monoxide-based reduction of iron (III) oxide (Fe2O3) and zinc ferrite (ZnOFe2O3)

TMS 2022 151st annual meeting & exhibition supplemental proceedings, Springer International Publishing, Cham (2022), pp. 917-926